|

The Causes

of Altitude Sickness

The

percentage of oxygen in the atmosphere at sea level is about

21% and the barometric pressure is around 760 mmHg (1 bar).

As altitude increases, the percentage remains the same but

the number of oxygen molecules per breath is reduced. The

percentage of oxygen in the atmosphere at sea level is about

21% and the barometric pressure is around 760 mmHg (1 bar).

As altitude increases, the percentage remains the same but

the number of oxygen molecules per breath is reduced.

At 3,600 metres (12,000 feet) the barometric pressure is only

about 480 mmHg (0.63 bar), so there are roughly 40% fewer

oxygen molecules per breath so the body must adjust to having

less oxygen.

In addition,

high altitude and lower air pressure causes fluid to leak

from the capillaries in both the lungs and the brain which

can lead to fluid build-up. Continuing on to higher altitude

without proper acclimatisation can lead to the potentially

serious, even life-threatening altitude sickness.

Acclimatisation Acclimatisation

The main

cause of altitude sickness is going too high too quickly.

Given enough time, your body will adapt to the decrease in

oxygen at a specific altitude. This process is known as acclimatisation

and generally takes one to three days at any given altitude,

e.g. if you climb to 3,000 metres and spend several days at

that altitude, your body will acclimatise to 3,000 metres.

If you then climb to 5,000 metres your body has to acclimatise

once again.

Several

changes take place in the body which enable it to cope with

decreased oxygen:

- The depth

of respiration increases.

- The body

produces more red blood cells to carry oxygen.

- Pressure

in pulmonary capillaries is increased, "forcing" blood into

parts of the lung which are not normally used when breathing

at sea level.

- The body

produces more of a particular enzyme that causes the release

of oxygen from haemoglobin to the body tissues.

Please

Note: There is NO substitute for proper acclimatisation!!

For

further information on the drugs used in mountain sickness

go to the Mountain Medicines page.

Cheyne-Stokes

Respirations

Above

3,000 metres (10,000 feet) most people experience a periodic

breathing during sleep known as Cheyne-Stokes Respirations.

The pattern begins with a few shallow breaths and increases

to deep sighing respirations then falls off rapidly even ceasing

entirely for a few seconds and then the shallow breaths begin

again. Above

3,000 metres (10,000 feet) most people experience a periodic

breathing during sleep known as Cheyne-Stokes Respirations.

The pattern begins with a few shallow breaths and increases

to deep sighing respirations then falls off rapidly even ceasing

entirely for a few seconds and then the shallow breaths begin

again.

During the period when breathing stops the person often becomes

restless and may wake with a sudden feeling of suffocation.

This can disturb sleeping patterns, exhausting the climber.

This type of breathing is not considered abnormal at high

altitudes. Acetazolamide is helpful in relieving

this periodic breathing.

Acute

Mountain Sickness (AMS)

AMS is very

common at high altitude. At over 3,000 metres (10,000 feet)

75% of people will have mild symptoms. The occurrence of AMS

is dependent upon the elevation, the rate of ascent, and individual

susceptibility. Many people will experience mild AMS during

the acclimatisation process. The symptoms usually start 12

to 24 hours after arrival at altitude and begin to decrease

in severity around the third day.

The

symptoms of Mild AMS include: The

symptoms of Mild AMS include:

- Headache

- Nausea

& Dizziness

- Loss

of appetite

- Fatigue

- Shortness

of breath

- Disturbed

sleep

- General

feeling of malaise

Symptoms

tend to be worse at night and when respiratory drive is decreased.

Mild AMS does not interfere with normal activity and symptoms

generally subside within two to four days as the body acclimatises.

As long as symptoms are mild, and only a nuisance, ascent

can continue at a moderate rate. When hiking, it is essential

that you communicate any symptoms of illness immediately to

others on your trip.

Moderate

AMS

The signs and symptoms of Moderate

AMS include:-

- Severe

headache that is not relieved by medication

- Nausea

and vomiting, increasing weakness and fatigue

- Shortness

of breath

- Decreased

co-ordination (ataxia).

|

|

Normal

activity is difficult, although the person may still be able

to walk on their own. At this stage, only advanced medications

or descent can reverse the problem. Descending only 300 metres

(1,000 feet) will result in some improvement, and twenty four

hours at the lower altitude will result in a significant improvement. Normal

activity is difficult, although the person may still be able

to walk on their own. At this stage, only advanced medications

or descent can reverse the problem. Descending only 300 metres

(1,000 feet) will result in some improvement, and twenty four

hours at the lower altitude will result in a significant improvement.

The person should remain at lower altitude until all the symptoms

have subsided (up to 3 days). At this point, the person has

become acclimatised to that altitude and can begin ascending

again.

The best

test for moderate AMS is to have the person walk a straight

line heel to toe just like a sobriety test. A person with

ataxia would be unable to walk a straight line. This is a

clear indication that an immediate descent is required. It

is important to get the person to descend before the ataxia

reaches the point where they cannot walk on their own (which

would necessitate a stretcher evacuation).

Severe

AMS Severe

AMS

Severe AMS

results in an increase in the severity of the aforementioned

symptoms including: Ÿ Shortness of breath at rest, Ÿ Inability

to walk, Ÿ Decreasing mental status, Ÿ Fluid build-up in the

lungs, Severe AMS requires immediate descent of around 600

metres (2,000 feet) to a lower altitude.

There are

two serious conditions associated with severe altitude sickness;

High Altitude Cerebral Oedema (HACO) and High Altitude Pulmonary

Oedema (HAPO). Both of these happen less frequently, especially

to those who are properly acclimatised. But, when they do

occur, it is usually in people going too high too fast or

going very high and staying there. In both cases the lack

of oxygen results in leakage of fluid through the capillary

walls into either the lungs or the brain.

High

Altitude Pulmonary Oedema (HAPO)

|

Symptoms

of HAPO include:-

-

Shortness

of breath at rest

-

Tightness

in the chest, and a persistent cough bringing up

white, watery, or frothy fluid

-

Marked

fatigue and weakness

-

A

feeling of impending suffocation at night

-

Confusion,

and irrational behaviour

|

HAPO

results from fluid build up in the lungs. This fluid prevents

effective oxygen exchange. As the condition becomes more severe,

the level of oxygen in the bloodstream decreases, which leads

to cyanosis, impaired cerebral function, and death. HAPO

results from fluid build up in the lungs. This fluid prevents

effective oxygen exchange. As the condition becomes more severe,

the level of oxygen in the bloodstream decreases, which leads

to cyanosis, impaired cerebral function, and death.

Sometimes HAPO is referred to as HAPE. They are both the same.

The difference is because of the different American spelling

(edema)

Confusion,

and irrational behaviour are signs that insufficient oxygen

is reaching the brain. One of the methods for testing yourself

for HAPO is to check your recovery time after exertion.

In cases of HAPO, immediate descent of around 600 metres (2,000

feet) is a necessary life-saving measure. Anyone suffering

from HAPO must also be evacuated to a medical facility for

proper follow-up treatment.

Have

you, or someone you know, ever suffered from HAPO or HAPE

(high altitude pulmonary oedema/edema)? Then join the "International

HAPE Database" a registry of previous HAPE sufferers

worldwide who might consider participating in future research

studies. Have

you, or someone you know, ever suffered from HAPO or HAPE

(high altitude pulmonary oedema/edema)? Then join the "International

HAPE Database" a registry of previous HAPE sufferers

worldwide who might consider participating in future research

studies.

High

Altitude Cerebral Oedema (HACO/HACE) High

Altitude Cerebral Oedema (HACO/HACE)

HACO is

the result of the swelling of brain tissue from fluid leakage.

Symptoms

of HACO include:-

It

generally occurs after a week or more at high altitude. Severe

instances can lead to death if not treated quickly. Immediate

descent of around 600 metres (2,000 feet) is a necessary lifesaving

measure. It

generally occurs after a week or more at high altitude. Severe

instances can lead to death if not treated quickly. Immediate

descent of around 600 metres (2,000 feet) is a necessary lifesaving

measure.

There are some medications that may be used for treatment

in the field, but these require proper training in their use.

Anyone suffering

from HACO must be evacuated to a medical facility for follow-up

treatment.

Prevention

of Altitude Sickness

This involves

proper acclimatisation and the possible use of medications.

|

Some

basic guidelines for the prevention of AMS:-

|

If

possible, don't fly or drive to high altitude. Start

below 3,000 metres (10,000 feet) and walk up. If

possible, don't fly or drive to high altitude. Start

below 3,000 metres (10,000 feet) and walk up.

- If

you do fly or drive, do not overexert yourself or

move higher for the first 24 hours.

- If

you go above 3,000 metres (10,000 feet), only increase

your altitude by 300 metres (1,000 feet) per day,

and for every 900 metres (3,000 feet) of elevation

gained, take a rest day to acclimatise.

- Climb

high and sleep low! You can climb more than 300 metres

(1,000 feet) in a day as long as you come back down

and sleep at a lower altitude.

- If

you begin to show symptoms of moderate altitude sickness,

don't go higher until symptoms decrease.

- If

symptoms increase, go down, down, down!

- Keep

in mind that different people will acclimatise at

different rates. Make sure everyone in your party

is properly acclimatised before going any higher.

- Stay

properly hydrated. Acclimatisation is often accompanied

by fluid loss, so you need to drink lots of fluids

to remain properly hydrated (at least four to six

litres per day). Urine output should be copious and

clear to pale yellow.

- Take

it easy and don't overexert yourself when you first

get up to altitude. But, light activity during the

day is better than sleeping because respiration decreases

during sleep, exacerbating the symptoms.

- Avoid

tobacco, alcohol and other depressant drugs including,

barbiturates, tranquillisers, sleeping pills and opiates

such as dihydrocodeine. These further decrease the

respiratory drive during sleep resulting in a worsening

of symptoms.

- Eat

a high calorie diet while at altitude.

- Remember:

Acclimatisation is inhibited by overexertion, dehydration,

and alcohol.

|

Please

Note: There is NO substitute for proper acclimatisation!!

Preventative

Medications

Acetazolamide

(Diamox): This is the most tried and tested drug for altitude

sickness prevention and treatment. Unlike dexamethasone (below)

this drug does not mask the symptoms but actually treats the

problem. It seems to works by increasing the amount of alkali

(bicarbonate) excreted in the urine, making the blood more

acidic. Acidifying the blood drives the ventilation, which

is the cornerstone of acclimatisation.

For prevention, 125 to 250mg twice daily starting one or two

days before and continuing for three days once the highest

altitude is reached, is effective. Blood concentrations of

acetazolamide peak between one to four hours after administration

of the tablets.

Studies

have shown that prophylactic administration of acetazolamide

at a dose of 250mg every eight to twelve hours before and

during rapid ascent to altitude results in fewer and/or less

severe symptoms (such as headache, nausea, shortness of breath,

dizziness, drowsiness, and fatigue) of acute mountain sickness

(AMS). Pulmonary function is greater both in subjects with

mild AMS and asymptomatic subjects. The treated climbers also

had less difficulty in sleeping. Studies

have shown that prophylactic administration of acetazolamide

at a dose of 250mg every eight to twelve hours before and

during rapid ascent to altitude results in fewer and/or less

severe symptoms (such as headache, nausea, shortness of breath,

dizziness, drowsiness, and fatigue) of acute mountain sickness

(AMS). Pulmonary function is greater both in subjects with

mild AMS and asymptomatic subjects. The treated climbers also

had less difficulty in sleeping.

Gradual

ascent is always desirable to try to avoid acute mountain

sickness but if rapid ascent is undertaken and actazolamide

is used, it should be noted that such use does not obviate

the need for a prompt descent if severe forms of high altitude

sickness occur, i.e. pulmonary or cerebral oedema.

Side

effects of acetazolamide include: an uncomfortable tingling

of the fingers, toes and face carbonated drinks tasting flat;

excessive urination; and rarely, blurring of vision.

On

most treks, gradual ascent is possible and prophylaxis tends

to be discouraged. Certainly if trekkers do develop headache

and nausea or the other symptoms of AMS, then treatment with

acetazolamide is fine. The treatment dosage is 250 mg twice

a day for about three days.

A trial

course is recommended before going to a remote location where

a severe allergic reaction could prove difficult to treat

if it occurred.

Dexamethasone (a steroid) is a drug that decreases

brain and other swelling reversing the effects of AMS. The

dose is typically 4 mg twice a day for a few days starting

with the ascent. This prevents most of the symptoms of altitude

illness from developing.

WARNING:

Dexamethasone is a powerful drug and should be used with caution

and only on the advice of a physician and should only be used

to aid acclimatisation by sufficiently qualified persons or

those with the necessary experience of its use.

For

further information on drugs to treat mountain sickness

go to the Mountain Medicines page.

Treatment

of AMS Treatment

of AMS

The only

cure for mountain sickness is either acclimatisation or descent.

Symptoms

of Mild AMS can be treated with pain killers for headache,

acetazolamide and dexamethasone. These help to reduce

the severity of the symptoms, but remember, reducing the symptoms

is not curing the problem and could even exacerbate the problem

by masking other symptoms.

Acetazolamide

allows you to breathe faster so that you metabolise more oxygen,

thereby minimising the symptoms caused by poor oxygenation

which is especially helpful at night when the respiratory

drive is decreased.

Acetazolamide may be obtained on prescription in the UK from

Doctor

Fox

Dexamethasone: This powerful steroid drug can be life

saving in people with HACO (HACE), and works by decreasing

swelling and reducing the pressure in the skull. The dosage

is 4 mg three times per day, and obvious improvement usually

occurs within about six hours. This drug "buys time" especially

at night when it may be problematic to descend. Descent should

be carried out the next day. It is unwise to ascend while

taking dexamethasone: unlike diamox this drug only masks the

symptoms.

Dexamethasone

can be highly effective: many people who are lethargic or

even in coma will improve significantly after tablets or an

injection, and may even be able to descend with assistance.

Many pilgrims at the annual festival at Gosainkunda lake in

Nepal suffer from HACO following a rapid rate of ascent, and

respond remarkably well to dexamethasone. Dexamethasone

can be highly effective: many people who are lethargic or

even in coma will improve significantly after tablets or an

injection, and may even be able to descend with assistance.

Many pilgrims at the annual festival at Gosainkunda lake in

Nepal suffer from HACO following a rapid rate of ascent, and

respond remarkably well to dexamethasone.

Mountain climbers also sometimes carry this drug to prevent

or treat AMS. It needs to be used cautiously, because it can

cause stomach irritation, euphoria or depression.

It

may be a good idea to pack this drug for a high altitude trek

for emergency usage in the event of HACO In people allergic

to sulpha drugs (and therefore unable to take diamox) dexamethasone

can also be used for prevention: 4 mg twice a day for about

three days may be sufficient.

Other

Medicines used for treating Altitude Sickness include:-

Ibuprofen

which is effective in relieving symptoms & altitude induced

headache. Ibuprofen

which is effective in relieving symptoms & altitude induced

headache.

Nifedipine:

This drug is usually used to treat high blood pressure. It

rapidly decreases pulmonary artery pressure and also seems

able to decrease the narrowing in the pulmonary artery caused

by low oxygen levels, thereby improving oxygen transfer. It

can therefore be used to treat HAPO, though unfortunately

its effectiveness is not anywhere as dramatic that of dexamethasone

in HACO. The dosage is 20mg of long acting nifedipine, six

to eight hourly.

Nifedipine can cause a sudden lowering of blood pressure so

the patient has to be warned to get up slowly from a sitting

or reclining position. It has also been used in the same dosage

to prevent HAPO in people with a past history of this disease.

Frusemide

may clear the lungs of water in HAPO and reverse the suppression

of urine brought on by altitude. However, Frusemide can also

lead to collapse from low volume shock if the victim is already

dehydrated. Treatment dosage is 120mg daily.

Breathing

· 100% Oxygen also reduces the effects of altitude sickness.

The

Gamow Bag

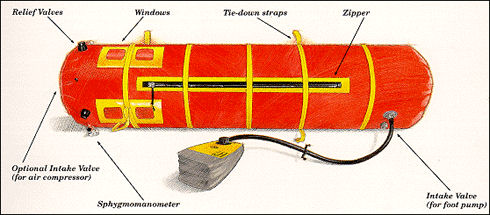

This

clever invention has revolutionised field treatment of altitude

sickness. The bag is composed of a sealed chamber with a pump. This

clever invention has revolutionised field treatment of altitude

sickness. The bag is composed of a sealed chamber with a pump.

The casualty is placed inside the bag and it is inflated by

pumping it full of air effectively increasing the concentration

of oxygen and therefore simulating a descent to lower altitude.

In

as little as 10 minutes the bag can create an "atmosphere"

that corresponds to that at 900 to 1,500 metres (3,000 to

5,000 feet) lower. After two hours in the bag, the person's

body chemistry will have "reset" to the lower altitude.

This acclimatisation lasts for up to 12 hours outside of the

bag which should be enough time to get them down to a lower

altitude and allow for further acclimatisation.

The

bag and pump together weigh about 6.5 kilos (15 pounds) and

are now carried on most major high altitude expeditions. Bags

can be rented for short term treks or expeditions.

|